Txt By Por Juan Balaguer

The rebellion of drawings

Article about Argentine artist Eduardo StupÃa, published in MOR Magazine number 11, december 2013

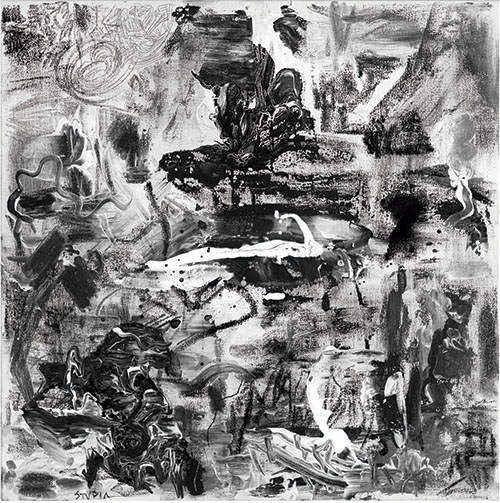

.jpg)

Eduardo Stupía is one of Argentina’s most relevant contemporary artists. In a scenery where the word “contemporary” is not referred to a chronological sense but to a way of creating art –based on solutions ostentatiously removed from the traditional arts, with an obligation of having complex conceptual frame, with an spectacular and onerous use of new technologies, with huge media deployment or with the intervention of armies of experts of such specific and dissimilar areas as engineering or taxidermy- Stupía manages to fill his seat in the fine arts world with its very essence: the drawings. There is one particularity though: In the work of Stupía the drawings are contemporary because they are intentionally removed from their role in the “fine arts”. The line confronts that cultural construction forged in the colouring books of our infancy; starts a revolution against the primary mandate of being the limit for a coloured surface (let’s paint “inside the line”); it rebels against the hierarchic submission and against subordination to the painting, considered in the past as necessary to transform that black and white piece of paper into a “finished work”. Drawing in Stupía's work does no longer consider itself merely as a previous step on the way to a larger work of art; instead, it throws itself to an independence epic and stands by its own. Permanently emancipated, the line and the surface (the stain) enjoy their autonomy. On the linen or on the page, the lines move, tangle up, attract or repel each other and build a work of art that comes and goes between abstraction and figuration.

Dialectic of drawings

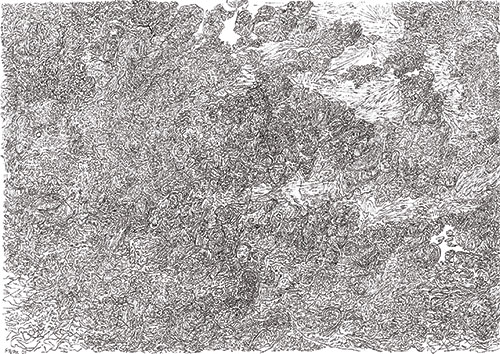

Some of his drawings, especially those made during his first stage, are figurative in a traditional way. The represented elements can be easily distinguished. Although they are usually set in sceneries that do not respect the occidental canon and the traditional vision about perspective, they use the space in a manner more similar to the oriental conception. Nevertheless, even in his “abstract” works, the most abundant, the drawing portrays a figurative being. In Stupía’s drawings is not the artist who draws the characters, the landscapes, the tress or the situations, but they are drawn in the mind of the spectator instead. Eduardo makes us draw in our heads, invites us to loose ourselves in the intricate maze of his strokes, his stains and his gaps until we can read stories. The prestigious art critic Fabián Lebenglik wrote in the catalogue for the retrospective show presented at the Recoleta Cultural Centre in 2006. “The work of Eduardo Stupía smartly plays with the trained eye, which is inevitably driven to over interpret lines, filigrees, stains and strokes. In that way of subtle imaginary correspondences, its wefts are shown like mirages in which every eye sets its own story”. Eduardo’s drawings can be looked at, but they can also be read.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Another particularity of Stupía's work resides on the always even distance between abstraction and figuration. Impossible to be classified, his drawings have no quarrel with the classic categories, but they absorb them instead. Abstraction or figuration? Writing or design? Drawing or painting? Signifier or significant? Stupía’s work is the chronicle of a road towards synthesis. But this is not a synthesis related to the basics, but quite the opposite, is the synthesis as in dialectics, that synthesis that widens its field until it may contain a whole that goes beyond conflicts and dichotomies.

The calligraphic signifier

Many prestigious critics and writers wrote about the closeness between writing and Stupía’s work. Saying that rivers of ink have been shed on this relationship would be an overstatement, but is a beautiful and useful image to illustrate this particular case’s material brotherhood between the drawing and the writing. It is very difficult to write about Eduardo’s work and not giving up to the temptation of theorising about languages, systems, alphabets and calligraphies.

By looking at any of his drawings, the gaze starts to run from one spot to the other. The composition skills with minimal resources –black, white, line, plane, emptiness- forces the eye to sequentially read the work of art in several directions. The Hebrew alphabet is read from right to left, the oriental calligraphy from top to bottom, the western writing from left to right. Stupía’s work, on the other hand, creates and recreates a system of its own, masterly driving the visual flow between lines, stains, colourful filigree and empty spaces. As real works of arts do, Stupía’s work builds its own system, invents its own paradigm and communicates its instructions at the same time that they are used. Some kind of visual symphony that transports us through allegros and silences until we feel that we are the ones who created the feeling and the story in front of each drawing. Eduardo’s work is also musical and narrative. It sounds and it tells.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Eduardo Stupía has always been related to writing: with the significant, as it’s easily perceivable in the surface of his drawings, but also with the signifier, as he worked a long time as an English translator. His curatorial, criticism and art texts are both sensitive and generous. For many years he collaborated with Diario de Poesía –the most important Latin American poetry publication, founded by his friend Daniel Samoilovich- with translations and articles. When, in 1992, the artist Juan Pablo Renzi, in charge of design and art for the publication, prematurely died, Eduardo took over his duties and became responsible for designing the newspaper. On a similar ground, he was in charge of designing the frontispiece of the books published by the editorial house Adriana Hidalgo, directed by Fabián Lebenglik. Draughtsman, critic, writer, translator and designer.

The multiple artist

When talking to Eduardo Stupía one may confirm what his story allows imagining: an attentive, mildly unsettled, alert personality, who knew how to sail the Argentinean cultural waters for the last 30 years getting inspiration, free of prejudice, from every possible stimulus. He always had a close relation with literature, poetry, visual arts and cinema. As if he was living five or six lives at the time, Stupía is a translator, a writer, a reader, a teacher, a movie expert, a designer, a suffering River Plate fan and, of course, an artist. If all this is not enough, during his formation years he flirted with music and drama. This prolific participation in the world of culture made him an acquaintance of the most relevant figures of the media since 1970 until today. In fact, is a circle to which he gained the right to be a part of. And this access was not due to a feverish labour, to the curious extravagances artists usually embody or to the power of his manifestos (which he indeed wrote), but because of the solidity and introspectiveness of his work, far from any type of fashion, tendency or movement like not many others. Completely original, persistent and attractive. A work that naturally demonstrates its cleverness. Is almost the same naturalness with which Eduardo assumes his role as a virtuous artist.

To clearly describe his personality, it would be enough to say that this draughtsman with a 40 year career, unanimously recognized by his colleagues and the critics, whose work is part of particular and museums' collections, for example New York’s MoMa, has been working as a “full time" artist only in the past four years. Until then, he divided his time between the work of an artist and several jobs. He was a book store employee, a freelance translator for several editorial houses, paperback writer for video’s covers and press director for cinema distributors among other jobs. A strategy that allowed him, apart from making a living, to always be in touch with the most simple of all words, the real world. An anchorage that never prevent him from being the prolific demiurge of his complex worlds built, like the most transcendental creations, with the most basic elements: ink and paper.

La rebelión del dibujo

ArtÃculo sobre el artista argentino Eduardo StupÃa publicado en la revista MOR, núm. 11, diciembre 2013

.jpg)

Eduardo Stupía es uno de los artistas contemporáneos más relevantes de la Argentina. En un escenario en que la palabra “contemporáneo” hace referencia no tanto a una marca cronológica como a un modo de crear arte –basado en resoluciones aparatosamente alejadas de las disciplinas artísticas tradicionales, con obligatorios y, a veces, enrevesados marcos conceptuales, con espectacular y onerosa utilización de nuevas tecnologías, con inmensos despliegues mediáticos o con la intervención de ejércitos de especialistas en disciplinas tan específicas como la ingeniería o tan curiosas como la taxidermia– Stupía se las arregla para ocupar su lugar con lo que es el hacer esencial de las “bellas artes”: el dibujo. Con una particularidad, en la obra de Stupía el dibujo es contemporáneo porque se aleja intencionalmente de su rol de “bella arte”. La línea se enfrenta con aquella construcción cultural de los libros para colorear de nuestra infancia; monta una revolución contra el mandato primario de ser límite de una superficie de color (pintada “sin pasarnos de la línea”), se rebela contra el sometimiento jerárquico, y la subordinación a la pintura, considerada hasta entonces necesaria para transformar esa hoja en blanco y negro en un “trabajo finalizado”. El dibujo en Stupía no se considera más a sí mismo como un paso previo en la concreción de una obra mayor, se lanza a la epopeya independentista y se sostiene por sí solo. Definitivamente emancipadas, la línea y el plano (la mancha) gozan con su autonomía. Se mueven, se enredan, se atraen y se repelen en la hoja o en el lienzo y construyen una obra que va y viene entre la abstracción y la figuración.

La dialéctica del dibujo

Algunos dibujos, en general los de su primera etapa, son figurativos en un sentido tradicional. Se pueden reconocer claramente los elementos representados. Aunque generalmente estén planteados en escenarios que no respetan el canon occidental y la visión de la perspectiva tradicional sino que hacen un uso del espacio más cercano a la concepción oriental. Sin embargo, aún en su obra “abstracta”, la más abundante, los dibujos tienen un ser figurativo. Aunque no es el artista quien dibuja los personajes, los paisajes, los árboles, las situaciones, sino la mente de quien mira. Eduardo nos hace dibujar en nuestra cabeza, nos invita a perdernos en el intrincado laberinto de sus trazos, sus manchas y sus vacíos hasta leer historias. En ocasión de su muestra retrospectiva del año 2006 en el Centro Cultural Recoleta de Buenos Aires, el prestigioso crítico Fabián Lebenglik escribió en su texto para el catálogo “La obra de Eduardo Stupía juega inteligentemente con la mirada entrenada del espectador, que inevitablemente es conducido a sobreinterpretar líneas, filigranas, manchas y pinceladas. En ese camino de sutiles correspondencias imaginadas, sus tramas se muestran como espejismos donde cada ojo pone sus historias”. Los dibujos de Eduardo se miran, pero también se leen.

En esta salomónica distancia entre abstracción y figuración radica otra de las peculiaridades de la obra de Stupía. Inclasificables, sus dibujos no batallan contra las categorías clásicas, sino que las fagocitan. ¿Abstracción o figuración? ¿Escritura o diseño? ¿Dibujo o pintura? ¿Significante o significado? La obra de Stupía es la crónica de un camino hacia la síntesis. Pero no hacia la síntesis entendida como reducción a lo básico, sino todo lo contrario, hacia la síntesis dialéctica, aquella que amplía su campo hasta contener un todo superador, eliminando conflictos y dicotomías.

El significante caligráfico

Muchos críticos y plumas prestigiosas escribieron sobre la cercana relación entre la escritura y la obra de Stupía. Sería exagerado decir que se han vertido ríos de tinta sobre esta relación, pero es una bella y útil imagen para graficar la hermandad material entre el dibujo y la escritura en este caso particular. Escribir sobre la obra de Eduardo y no caer en la enorme tentación de teorizar acerca de lenguajes, sistemas, alfabetos y caligrafías es casi una quimera.

Al mirar cualquiera de sus dibujos, la mirada comienza a correr desde un sector a otro de la superficie. La destreza compositiva aplicada con recursos mínimos –blanco, negro, línea, plano, vacío– hace que el ojo lea secuencialmente la obra en distintas direcciones. El alfabeto hebreo se lee de derecha a izquierda, la caligrafía oriental, de arriba hacia abajo, la escritura occidental, de izquierda a derecha. Las obras de Stupía, en cambio, crean y recrean su propio sistema, manejando con maestría el flujo visual entre zonas de abigarrada filigrana, líneas, manchas y espacios blancos. Como las verdaderas obras de arte, construyen su propio sistema, inventan su paradigma, comunican sus instrucciones de uso al mismo tiempo que son utilizadas. Una especie de sinfonía visual que nos transporta entre allegros y silencios hasta hacernos sentir que nosotros mismos construimos la sensación y el relato frente a cada dibujo. La obra de Eduardo es también musical y narrativa. Suena y cuenta.

Eduardo Stupía estuvo siempre relacionado con la escritura: con el significante, como es fácil percibir en la superficie de sus trabajos, pero también con el significado, ya que ha trabajado durante mucho tiempo como traductor de inglés. Sensibles y generosos son también sus textos de arte, críticos y curatoriales. Durante muchos años colaboró con el Diario de Poesía –la más importante publicación de poesía de América Latina, fundada por su amigo Daniel Samoilovich–, con traducciones y artículos. Cuando el artista Juan Pablo Renzi, responsable del diseño y la dirección de Arte del Diario falleció prematuramente en 1992, Eduardo asumió las tareas y se convirtió en el responsable del diseño de la publicación. En un terreno similar, también fue responsable del diseño de las portadas de los libros de la editorial Adriana Hidalgo, dirigida por Fabián Lebenglik. Dibujante, crítico, escritor, traductor, y diseñador.

El artista múltiple

Una charla con Eduardo Stupía ratifica lo que su historia permite imaginar: una personalidad atenta, apaciblemente inquieta, despierta, que supo moverse en la escena cultural argentina de los últimos 30 años alimentándose, libre de prejuicios, de cada estímulo posible. Literatura, poesía, cine, artes visuales, tuvieron siempre un punto de contacto en él. Como si viviera cinco o seis vidas en una, Stupía es traductor, escritor, lector, docente, experto en cine, diseñador, sufrido hincha de River Plate y, por supuesto, artista. Como si esto fuera poco, durante sus años de formación también pasó por experiencias con la música y el teatro. Esta prolífica participación del mundo de la cultura lo llevó a relacionarse con la mayoría de los actores relevantes del medio desde el año 1970 hasta hoy. De hecho, es un círculo del que se ha ganado el derecho a formar parte. Y no por una afiebrada militancia ni por las curiosas extravagancias a las que nos tienen acostumbrados los artistas ni por la potencia de sus manifiestos (que sí los ha escrito), sino por la autoría de una obra sólida e introspectiva, alejada de cualquier tipo de moda, tendencia o movimiento como pocas otras. Completamente original, perseverante y atractiva. Una obra que exhibe su inteligencia con total naturalidad. Casi la misma con la que Eduardo asume su rol de artista virtuoso.

Para describir claramente su personalidad, basta contar que este dibujante de más de 40 años de trayectoria, reconocido de forma unánime por sus colegas y por la crítica, cuya obra forma parte de numerosas colecciones particulares y museos –como, por ejemplo, el MoMA de Nueva York–, recién se dedica “full time” al arte desde hace 4 años. Hasta entonces, repartió su tiempo entre la tarea de artista y varios trabajos. Fue empleado en librerías, traductor free lance para distintas editoriales, redactor de cubiertas de video y director de prensa para distribuidoras de cine, entre otros trabajos. Una estrategia que le permitió, además de la superviviencia, estar siempre con los pies en la tierra, en el más llano de los mundos: el real. Un anclaje que nunca le impidió ser el prolífico demiurgo de sus complejos mundos construidos, como las creaciones trascendentes, con los elementos básicos: tierra y agua, o, en este caso, tinta y papel.